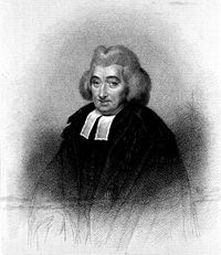

George Campbell (1719-1796)

George Campbell, the son a Presbyterian minister, was born in Aberdeen on Christmas Day 1719, a religious festival that at the time went unobserved by Scottish Calvinists. At the age of fifteen, Campbell attended Marischal College, one of two local universities, where he studied logic, metaphysics, pneumatology (philosophy of mind), ethics, and natural philosophy (physics). After graduating M.A. in 1738, Campbell went to Edinburgh and became apprenticed in the law. At the same time he attended divinity lectures at the University of Edinburgh, and this stimulated his interest in theological questions. As a result, once his apprenticeship was completed, he returned to Aberdeen and enrolled as a divinity student at both King's College and Marischal. Since the city of Aberdeen became actively caught up in the suppression of the Jacobite uprising in 1745, Campbell's divinity examinations were delayed until 1746. He received his license to preach in that year, and within two years was ordained to at the parish of Banchory Ternan just outside Aberdeen.

It was as a parish minister that George Campbell embarked on his lifelong project of translating the Gospels from the Greek, and also while a minister that he wrote the first two chapters of a subsequently well regarded book on The Philosophy of Rhetoric. After ten years in rural Aberdeenshire, Campbell was offered a parish within the city, and this brought him into contact with the intellectual community in northeast Scotland that was increasingly playing its part in the Scottish Enlightenment. In 1759, he was offered, and accepted, the position of principal at Marischal College and fully immersed himself in university affairs.

Along with Thomas Reid at King’s College, Campbell was a founding member of the Aberdeen Philosophical Society, popularly known as ‘the Wise Club’. The Club was not confined to philosophers in the modern sense. Its founders included the mediciner John Gregory and the naturalist David Skene, but the best known works to emerge from its deliberations were indeed primarily works of philosophy -- Reid's Inquiry into the Human mind, on the Principles of Common Sense (1764), James Beattie's Essay on the Nature and Immutability of Truth (1770), and Alexander Gerard's Essay on Genius. Campbell continued to work on the Philosophy of Rhetoric, sections of which he read to the Society. It was not finally published until 1776, three years after the Club had ceased to meet. The Philosophy of Rhetoric has a practical educational purpose, but it engages in the unmistakable Scottish Enlightenment project of a ‘science of human nature’, as well as revealing the influence of Reid’s philosophical conception of ‘common sense’.

Fourteen years before that, Campbell published his first major book -- A Dissertation in Miracles (1762). The philosophy of David Hume was a regular topic of discussion at the Wise Club and in this book Campbell took issue with the attack on miracles that Hume had launched in An Enquiry concerning Human Understanding. Campbell’s criticism of Hume, in contrast to the somewhat hysterical tone of Beattie’s later Essay, was judicious and respectful. The book was well received and led to Campbell succeeding the venerable Alexander Gerard as Professor of Divinity at Marischal in 1770. The lectures on church history and on preaching that he gave in this position were later published. After the publication of The Philosophy of Rhetoric (1776), George Campbell finally completed his translation of The Four Gospels. Ill health forced him into retirement shortly afterwards, and he died in 1796, the same year as Thomas Reid.

Like several other philosophers who were prominent in the Scottish Enlightenment, Campbell’s works circulated widely, and then in a relatively short period of time disappeared almost completely. A recent full length study of Campbell by Jeffrey M Suderman concludes that ‘the limits of the moderate mind’ that Campbell exemplifies to perfection ‘were intimately related to the limits of the enlightened mind’ with the result that ‘the fall of the Enlightenment entailed the fall of Christian moderatism’. Campbell’s Philosophy of Rhetoric is undoubtedly a product of this moderatism, and as such can probably only be read today out of historical interest. But some philosophical interest has revived in his Dissertation on Miracles because of its relevance to contemporary epistemological debates about testimony.

Enlightenment Philosophers

- Alexander Gerard ((1728-1795)

- Gershom Carmichael (1672-1729)

- Archibald Campbell (1691-1756)

- Francis Hutcheson (1694-1746)

- Henry Home, Lord Kames (1696-1782)

- Robert Wallace (1697-1771)

- George Turnbull (1698-1748)

- Thomas Reid (1710-1796)

- David Fordyce (1711-1751)

- David Hume (1711-1776)

- James Burnett, Lord Monboddo (1714-1796)

- Hugh Blair (1718-1800)

- George Campbell (1719-1796)

- William Robertson (1721-1793)

- Adam Smith (1723-1790)

- Adam Ferguson (1723-1816)

- John Millar (1735-1801)

- James Beattie (1735-1803)

- Dugald Stewart (1753-1828)

- Archibald Alison (1757-1839)